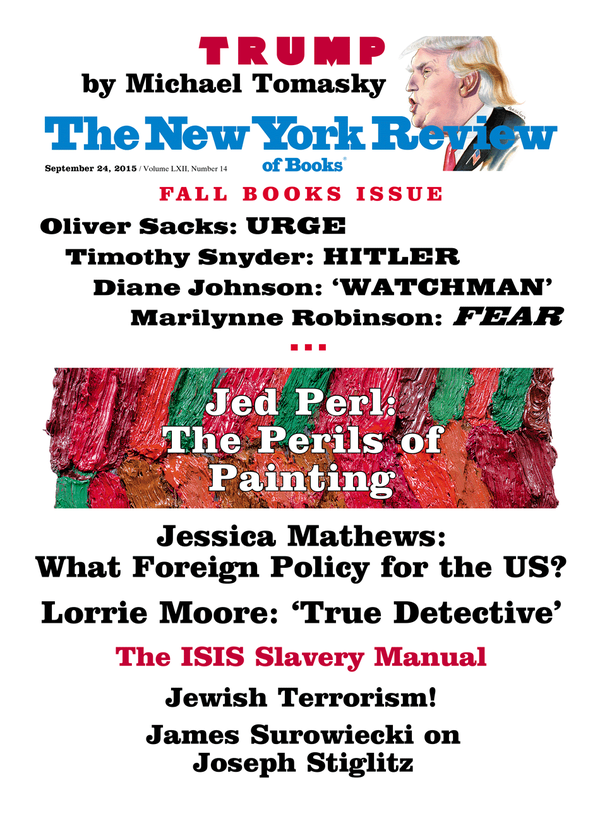

I was pleased to be included in Jed Perl’s article about contemporary painting in The New York Review of Books. The article was featured on the cover, illustrated by a detail of the painting “Night Table.” The painting was also reproduced in the text. An excerpt from the article is below. Click here for a PDF of the full text.

Jed Perl

The Perils of Painting Now

… Sincerity and authenticity must be communicated through a pictorial struggle, through the ways that stylistic traditions and qualities of line, color, and composition are embodied, enriched, and transformed…

One younger painter I think is really grappling with these difficult questions is Brett Baker. He was born in 1973 and has been showing his abstract canvases at the Elizabeth Harris Gallery in recent years. I have seen these small, heavily impastoed pictorial inventions a couple of times, with deepening interest and admiration. Their tight-packed, elongated rectangular forms—which are invariably based on a rather simple grid—bring to mind some of the layered compositions of Paul Klee as well as some of the textiles of Anni Albers. Working with orchestrations of jewel-rich blues, purples, and reds or forest-deep greens, oranges, and browns, Baker builds images that are simultaneously luxuriant and austere; the thickness of the paint is set in a tension with the limited nature of his structures. The vertically and diagonally aligned strokes of paint suggest geological layerings. The paintings have a Limoges-enamel intimacy.

I report my impressions of Baker’s paintings in a speculative spirit. He sets his work securely within a tradition of geometric abstraction, and he embraces that tradition with a virtuosity that leaves us at the very least with a sense of his deep and considered commitment—with a sense of his sincerity. He carries off his chosen style with considerable panache. As for the more complex question of meaning, of emotion—of the work’s truth to something within—I feel it remains an open question. My second encounter with Baker’s work in a couple of years suggests that its style, however limited, registers an emotional amplitude through the growing confidence of his stained-glass color, with its plangent, mysterious tonalities.

Much of the trouble in the visual arts today comes from our increasing dependence on the Internet, where all the richness and complexity of an artist’s painterly surfaces is reduced to pixels. Paintings are flattened out by the Internet. And the paintings that “take” to digital reproduction almost invariably trump the ones that demand the direct response of a human eye. The Internet, with its clicks and links, threatens to deny us the gradual, evolving, unmediated acquaintance with an artist’s actual work that I’ve had with Baker’s. In order to understand an artist’s work, we need repeated opportunities to see how qualities of surface and texture—what might be called facture—do and do not reflect deeper impulses.